Introduction:

Over the last 10 years or so, there have been a growing number of cocaine users exposed to opioid contamination or adulteration of their cocaine in the USA (4,5,12). Anecdotally, there has recently been an uptick, with multiple recent opiate overdoses in people who are reporting only crack, methamphetamine or cocaine use. In one case, a patient had an oxygen saturation of 8% about 10 minutes after the patient had been initially evaluated, and about an hour after he had received narcan by EMS. On initial presentation exam revealed AOx3, mydriatic pupils, and tachypnea as well as diaphoresis presumably from cocaine or other sympathomimetic use. Shortly after, the patient became bradycardic, from a heart rate of 120 bpm down to 40 bpm. 2mg of narcan was administered and the patient was started on a narcan drip. The patient admitted only cocaine use at a party prior to presentation and no knowledge of opiate ingestion or intentional use.

Definitions:

Speedball: a mixture of cocaine or methamphetamine and an opiate, either intentionally or unintentionally. This creates a more euphoric high, as well as increased addiction potential. Traditionally the most common opiate used has been heroin, however fentanyl is becoming more common.

Crack Lung: acute interstitial alveolar damage after freebasing/smoking crack cocaine, on a spectrum of disease ranging from mild infiltrate to ARDS in severe cases (14).

Crack cocaine: Cocaine that is boiled down with usually bicarbonate forming a solid rock (15).

Clinical significance:

While deaths from cocaine alone have been relatively stable, deaths from speedballs are ramping up exponentially based on previous data (1). Philadelphia was hit very hard back in 2018 with a large surge in deaths and overdoses, in one day having a reported 18 unknown opiate overdoses in cocaine using patients (4). New York was also hit very hard, with a 2000% increase in the years of 2010-2019 (5). More recently, in 2019-2020 the Fresno area was hit hard with a very similar situation of fentanyl overdoses in cocaine use (12). Illicit drug producers are increasingly mixing fentanyl into cocaine that they are selling, and year after year crime labs are reporting increased prevalence of the mixture (3). Worse, the amount of fentanyl required to cause an overdose is very small. As a frame of reference, a potentially fatal dose of fentanyl is roughly the size of Lincoln’s face on the penny, making it very easy to overdose unintentionally (6).

Fentanyl and opiates:

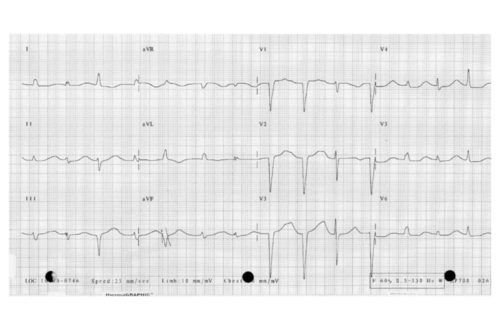

Fentanyl is 100 times more potent than morphine per weight; A dose of 2-3 mg of fentanyl is equivalent to 200-300 mg of morphine (2). Despite numerous unsubstantiated reports of first responder exposure, fentanyl cannot be absorbed through the skin in powder form (6). Symptoms of fentanyl overdose are similar to those of other opiate overdoses with miosis, bradypnea, hypopnea, mental status depression, nausea and vomiting. Less commonly, you can see QT prolongation with methadone, seizures with tramadol, and serotonin syndrome from meperidine (7). Constipation and urinary retention are common symptoms of long-term use. Acute overdoses can cause pulmonary edema and ARDS (so can cocaine/crack cocaine smoking and naloxone administration) (8). While not traditionally thought of as an opioid, a large amount of loperamide can also cause an opiate euphoria with severe QT prolongation and dysrhythmias, particularly with coingestion of a p-glycoprotein inhibitor such as amiodarone, azithromycin, verapamil (13). Overdoses (similar to other opioid overdoses) have been reported, particularly in children (9). When you see a potential opiate overdose, other presentations may mimic this including: clonidine (which may respond to narcan administration), seizures, CO toxicity, GHB, Baclofen, stroke, DKA, electrolyte derangements, etc. Workup depends on history. No history will lead to a broader workup: tylenol, salicylates, etoh, metabolic panel for organ damage and electrolyte derangements, acidemia or alkalemia, blood gas, CK, chest x-ray, ekg, b-hcg if pertinent, ct head for evaluation of any bleeding/stroke, ekg, urine drug screen, and expand on clinical judgment for any undifferentiated altered mental status or bradypnea patients. Patients should be monitored with end tidal CO2, O2 saturation, respiratory rate. Because the primary cause of morbidity/mortality in the acute opioid overdose is respiratory depression and failure, acute treatment of a suspected opioid overdose should focus on ventilation first along with concurrent administration of narcan. Recommended initial dosing of narcan in a suspected naive user with minimal respiratory depression is 0.4mg narcan, repeated every 3 minutes as necessary for a total of 10mg, and for the chronic user 0.05mg pushes (7). In a patient that is apnic or near-apnea, doses of 1-2mg are recommended (7). Pediatric dosing of narcan is 0.005mg-0.01mg/kg every 2-3 minutes for reversal of respiratory depression (10). Narcan has a relatively short half-life and typically the effect only lasts up to about 90 minutes, while the effects of opioids may last much longer. It’s vital to continue to monitor the patient’s respiratory status closely as respiratory depression can rapidly reoccur, requiring further doses of narcan (7). Concerning signs of recurrent respiratory depression requiring retreatment with narcan include a rising end tidal CO2, reduction in tidal volume, decreasing respiratory rate, and decreasing O2 saturation. If repeat doses of narcan are required, it is recommended to start the patient on a continuous infusion of ⅔ the total dose required to reverse their respiratory depression administered over an hour (7). Disposition may depend on which opioid the patient is exposed to. Morphine is long acting and requires 24 hours observation on telemetry, whereas evidence suggests that heroin overdoses can be discharged if after 2 hours post last narcan dose they are: ambulatory, GCS 15, O2 saturations over 92%, HR over 50, and euthermic (7). Other opiate overdoses should be observed for 4-6 hours with similar rules as heroin for discharging after observation (7). All patients who present with an opiate overdose should be offered narcan to take home with them, and some states are now requiring physicians who come into contact with opiate overdoses to offer it. At our institution, they should be offered a referral to Bridge Clinic as well if they would like to try and achieve sobriety.

Cocaine:

A cocaine intoxication will present with the classic sympathomimetic presentation of tachycardia, hypertension, mydriasis, diaphoresis, delirium, hyperthermia, eye pain choreoathetoid movements (11). Other findings can include chest pain, rhabdomyolysis leading to renal failure, stroke, dissection, heart failure, and ischemia (11). Symptoms may depend on the route of exposure; Nasal bridge deformities for snorting, increased risk of infections, HIV, and Hepatitis with IV use, pulmonary damage and “crack lung” if inhaled. Overdoses lead to worsening of their sympathomimetic symptoms, as well as increased risk of end organ damage. Differential diagnosis when evaluating an acute cocaine intoxicated patient include: MDMA, PCP, amphetamines, bipolar mania, other drugs of abuse, etc (11). Evaluation may include: blood count (eosinophilia is common), metabolic panel, troponin, EKG, creatinine kinase, coagulant factors (11). If you are concerned for a secondary end organ ischemia, evaluate that as well; CTA abdomen for mesenteric ischemia, CTA chest, abdomen, and pelvis for a dissection, CXR for SOB and possible crack lung/congestive heart failure/pneumothorax, IOP for possible angle closure glaucoma if indicated (11). Urine drug screens are generally accurate for cocaine, however, can be negative after 72 hours (11). Treatment of the cocaine intoxication should be with benzodiazepines for agitation, and active cooling for severe hyperthermia. For temperatures >106℉ the patient should be paralyzed with a non-depolarizing agent in conjunction with active cooling measures (11). For hypertensive emergencies, treat with benzodiazepines along with phentolamine (alpha blockade) or nitroprusside (smooth muscle relaxation) for blood pressure control (11). Wide complex tachycardias should be treated with sodium bicarbonate 1-2meq/kg bolus (cocaine causes sodium channel blockade) (11). For refractory tachycardias, administration of lidocaine has been efficacious (11). Catheterization is the safest option for STEMI, and consultation should be made if possible prior to receiving thrombolytics (11). Admission to telemetry should be considered for end organ ischemia or complications like chest pain, AKI, rhabdo, etc (11). Patients may be discharged home if showing no complications (11).

The Speed-Ball:

Now comes the difficult part. There are not many resources on how to treat these effectively and how they interact in the acute setting. Primarily, these patients will present in respiratory failure with an opiate toxidrome, however may show a mixed picture with mydriatic pupils, diaphoresis, and tachycardia. One of my recent patients followed this mixed picture, with respiratory failure while showing a sympathomimetic presentation. This paints a complicated picture, as many of us use miosis helping aid in the diagnosis of an opiate induced bradypnea. He did respond with narcan administration, showing a mild cocaine toxidrome while the narcan was still affecting his system. He later became bradycardic, however that was associated with an oxygen saturation of 8%, and so may have been secondary to severe hypoxia in a peri-arrest patient. As such, the most immediate life threat is likely to be secondary to respiratory failure from the opiate ingestion, and so this should be addressed first. Ventilate the patient, and if unstable increase rate and volume of bagging to wash out their CO2 and respiratory acidemia. Administration of narcan should be done carefully, 2mg may be needed but be prepared for the withdrawal. The best approach, as with any opioid overdose, is to give the minimum amount of narcan necessary to reverse the respiratory depression without inducing withdrawal, or even full consciousness. This reduces the risk of agitation and withdrawal exacerbating the clinical picture. After narcan administration the patient’s respiratory status should be monitored very carefully, as the sympathomimetic symptoms can mask the symptoms of the opiate overdose. My patient that almost died appeared like a mildly syndromic cocaine intoxication 10 minutes prior to their respiratory failure, and almost an hour and a half after the initial narcan administration he became bradypneic again.

On the other side of the spectrum, in the acutely agitated patient, the usual treatment of cocaine induced agitated delirium, benzodiazepines, can be complicated in the mixed toxidrome picture if the patient has an unknown opiate on board. Once control of the agitation is achieved, the often copious amount of benzodiazepines required may exacerbate the underlying and previously hidden opioid toxicity. In a recent case of a violent agitated delirium patient, we chose to use geodon to control the agitation, however, antipsychotics in the acute cocaine intoxication agitation is risky; seizure threshold is often affected, QT and QRS are often affected, and there is a possibility of mixing anticholinergic and sympathomimetic effects. While all of this sounds confusing and complicated, the best approach is to not overthink the situation and to treat the patient you have in front of you. Both opioid and sympathomimetic toxicities can be fatal and should be addressed independently. If the patient has bradypnea, hypoxia, or an elevated EtCO2, treat with narcan. If the patient is hyperthermic, agitated and delirious, treat with benzos. The patient should be closely monitored with the expectation that recurrent respiratory depression and/or agitation may likely occur, and you should be prepared to treat any symptoms unmasked by your interventions.

Disposition depends on symptoms and treatment requirements as always. Monitoring end tidal CO2 and oxygenation saturations should be continued. Those requiring narcan drips for recurrent respiratory failure or severe pathology should have an ICU consultation. Admission should be considered for any symptomatic speedball ingestions; evidence of opiate toxicity that is requiring multiple doses of narcan, having end organ ischemia from the cocaine toxicity, or any mixed picture.

Conclusion:

Anecdotally the recent slew of symptomatic speedball ingestions haven’t been chronic opiate users. They’ve been cocaine users with accidental ingestions: teenagers out partying, crack cocaine users, etc. They aren’t sure as to what happened, and their cohort isn’t sure either. They don’t know what is being mixed in, making the situation more confusing and dangerous for them and those around them. Be upfront but gentle, discuss with them what happened and inform them that whatever they used had opiates in it so they know not to continue using/mixing illicit substances. As said earlier, treat each individually and follow each disposition plan per individual intoxication.

Bibliography:

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Overdose Death Rates. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Published January 20, 2022. https://nida.nih.gov/drug-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates

- Broglio K, Portenoy R. Approximate Dose Conversions. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/image?imageKey=PALC%2F111216&topicKey=PALC%2F86302&source=see_link. Published 2021. Accessed May 26, 2022.

- Yerby N. Drug Traffickers are Increasingly Mixing Fentanyl Into Cocaine. Published July 10, 2019. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.addictioncenter.com/community/traffickers-mixing-fentanyl-cocaine/

- Thompson D. Fentanyl-laced crack cocaine a deadly new threat. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/addiction/news/20181031/fentanyl-laced-crack-cocaine-a-deadly-new-threat#1. Published October 31, 2018. Accessed May 26, 2022.

- Opioid Prevention Program. Opioid-related Data in New York State. https://health.ny.gov/statistics/opioid/. Published July 2021. Accessed May 26, 2022.

- Fentanyl facts. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/stopoverdose/fentanyl/index.html. Published February 23, 2022. Accessed May 26, 2022.

- Opioid toxicity. WikEM. https://www.wikem.org/wiki/Opioid_toxicity. Accessed May 26, 2022.

- Sterrett C, Brownfield J, Korn CS, Hollinger M, Henderson SO. Patterns of presentation in heroin overdose resulting in pulmonary edema. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2003;21(1):32-34. doi:10.1053/ajem.2003.50006

- Arnold C, Martinez CJ. Loperamide overdose. Cureus. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6663275/. Published May 25, 2019. Accessed May 26, 2022.

- Naloxone. WikEM. https://www.wikem.org/wiki/Naloxone. Accessed May 26, 2022.

- Cocaine toxicity. WikEM. https://wikem.org/wiki/Cocaine_toxicity. Accessed May 26, 2022.

- Armenian P, Whitman JD, Badea A, et al. notes from the field: unintentional fentanyl overdoses among persons who thought they were snorting cocaine — Fresno, California, January 7, 2019. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2019;68(31):687-688. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6831a2

- Inhibitors and inducers of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) drug efflux pump (P-gp multidrug resistance transporter). UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/image/print?imageKey=EM%2F73326&topicKey=RHEUM%2F1666&source=see_link. Published 2022. Accessed May 26, 2022.

- Forrester JM, Steele AW, Waldron JA, Parsons PE. Crack Lung: An acute pulmonary syndrome with a spectrum of clinical and histopathologic findings. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1990;142(2):462-467. doi:10.1164/ajrccm/142.2.462

- Authored by Editorial StaffLast Updated: May 13 2022. Crack vs cocaine: What’s the difference between Crack & Cocaine? American Addiction Centers. https://americanaddictioncenters.org/cocaine-treatment/differences-with-crack. Published May 13, 2022. Accessed May 26, 2022.

This Post Has 0 Comments